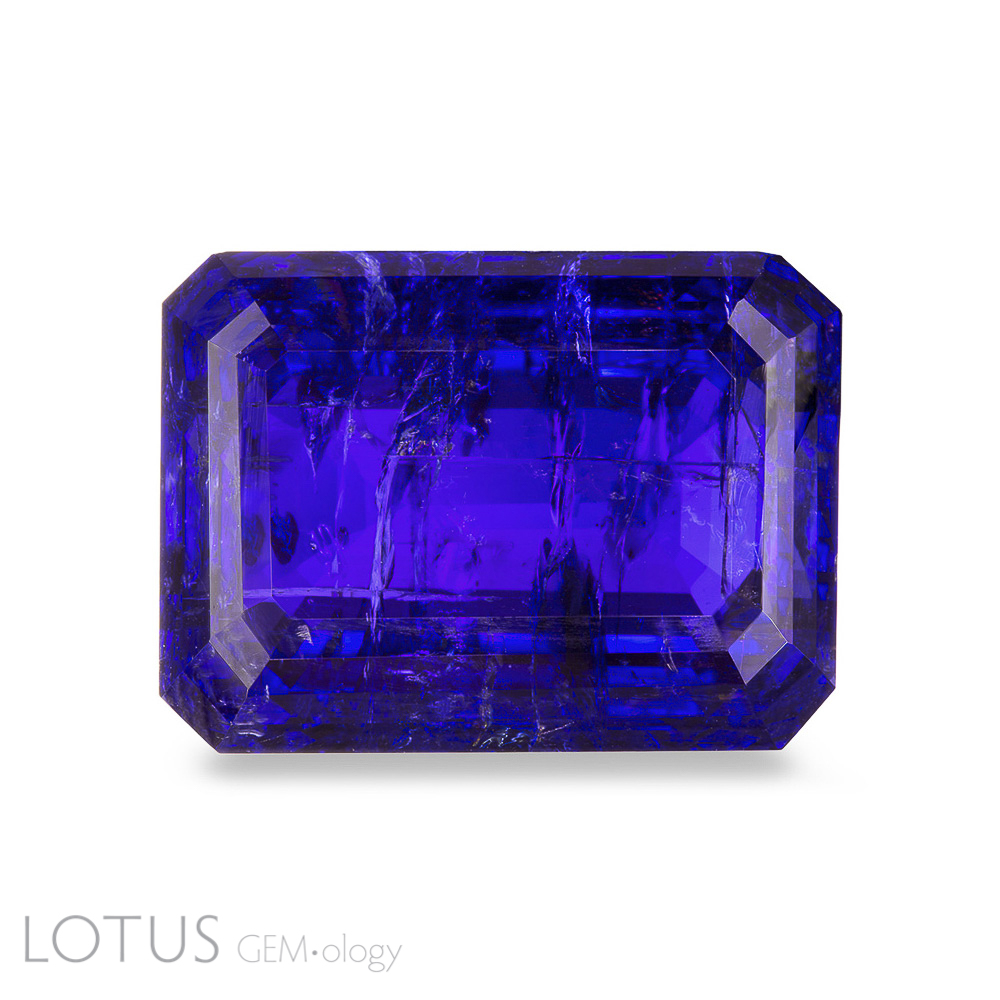

When a red spinel and a tanzanite were submitted for testing, oil was found in the fissures. Removal of the oil resulted in a startling deterioration in clarity.

Introduction

When it comes to the clarity enhancement of gems with oils/resins, a common belief is that the refractive index (RI) match between the host gem and the filler is critical. During the 1990s, the use of Opticon (n = 1.545) instead of cedarwood oil (n=1.512) was said to be vastly superior in masking fissures in emeralds (Hughes, 1998). If one follows this logic, it would seem that using oils or resins to clarity enhance something like a corundum (n=1.76) or spinel (n=1.72) would not be at all effective, since there is a yawning gap in RI between those gems and that of any oil or resin.

Certainly Burmese gem traders have never bought into that idea, for we regularly encounter oiled rubies, sapphires and spinels from Myanmar (Lotus Gemology, 2015). In fact, Burmese traders have told us that it is a common practice to immediately immerse rough into oil after it is unearthed. This is done not just to make viewing the interior easier, but primarily because it significantly enhances the gem's clarity. In our experience, such treatment is almost never disclosed to buyers.

In 2013, while visiting various mines and markets in Myanmar's Mogok Stone Tract, we asked if anyone was doing heat treatment, and were then taken to a small house where a man was heat-treating spinel. Gems were placed in a crucible and heated for a period of time. Then, while still relatively hot, they were dumped into a vessel containing – wait for it – red oil. It was a remarkable piece of performance art. After the oil was wiped off, we could discern no change in color from the heating.

Figure 1. Residue from the red oil that spinels were dumped into following heat treatment in Mogok, Myanmar witnessed by the author in 2013. Photo: E. Billie Hughes. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Figure 1. Residue from the red oil that spinels were dumped into following heat treatment in Mogok, Myanmar witnessed by the author in 2013. Photo: E. Billie Hughes. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Figure 2. Bojan brand “King Ruby Red Oil” from Chanthaburi, Thailand, along with a parcel of rough Thai rubies purchased by the author in 2016. Note the red stain on the plastic bag that the rubies were placed in. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul. Click on the photo for a a larger image.

Figure 2. Bojan brand “King Ruby Red Oil” from Chanthaburi, Thailand, along with a parcel of rough Thai rubies purchased by the author in 2016. Note the red stain on the plastic bag that the rubies were placed in. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul. Click on the photo for a a larger image.

Oil slicked spinel

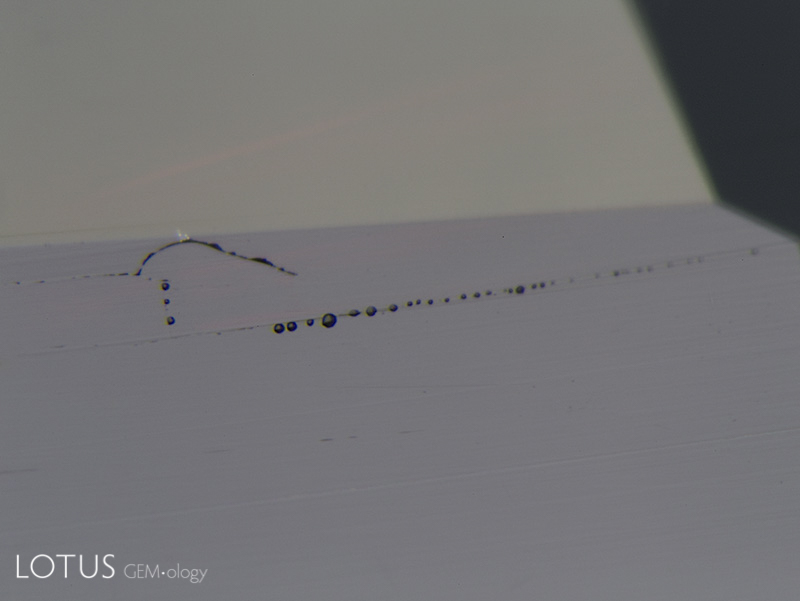

Because of the prevalence of oiling, we now check every stone with fissures for oil, no matter what the origin or type of gem. This is typically done with a hot point under the microscope (Figure 3). The hot point gently heats the gem to the point where, with oiled stones, the oil will leak out of the fissure in beads on the surface following the opening of the fissure (Figure 4).

Figure 3. The hot points used by Lotus Gemology are actually soldering irons with the narrowest possible tips. At their highest settings, they reach temperatures of about 400–500°C. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Figure 3. The hot points used by Lotus Gemology are actually soldering irons with the narrowest possible tips. At their highest settings, they reach temperatures of about 400–500°C. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Figure 4. Oil coagulating on the surface of a Burmese ruby after gentle heating with the hot point. Note how the oil droplets follow the fissure opening. Reflected light. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Figure 4. Oil coagulating on the surface of a Burmese ruby after gentle heating with the hot point. Note how the oil droplets follow the fissure opening. Reflected light. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

With the exception of emerald, customers purchasing colored gems are not expecting them to be clarity enhanced. As one major Bangkok trader told us several years ago: "I cannot sell an oiled spinel." For this reason, when we determine that a gem other than emerald has been fissure-filled with an oil or resin, we notify the client and allow them two opportunities to remove the filler before we issue the report.

In September 2020, Lotus Gemology received a 3-carat gem for identification. Inclusions and other testing showed that this stone was a spinel that originated from Myanmar's Mogok Stone Tract. We noticed a fissure on the pavilion running parallel to the girdle plane and application of the hot point caused oil to leak out. The client then retrieved the gem and went through one round of oil removal. During the recheck, we found the oil was still there, and so it went for the second round of oil removal. When the gem was returned to us, the difference was truly remarkable. Now the gem was disfigured by a highly reflective eye-visible fissure (Figure 5).

Figure 5. On the left is the 3-ct spinel as it was initially submitted. At right is the same stone following removal of the oil. The difference is striking. Following cleaning, a large reflective fissure is visible parallel to the girdle plane. This clearly demonstrates the ability of an oil/resin to mask fissures even when there is no close match in refractive index between the filler and host. Photos: Chanon Yimkeativong/Lotus Gemology.

Figure 5. On the left is the 3-ct spinel as it was initially submitted. At right is the same stone following removal of the oil. The difference is striking. Following cleaning, a large reflective fissure is visible parallel to the girdle plane. This clearly demonstrates the ability of an oil/resin to mask fissures even when there is no close match in refractive index between the filler and host. Photos: Chanon Yimkeativong/Lotus Gemology.

Conclusion

Figures 5 and 6 clearly demonstrate that oil can have a significant impact on the clarity of a gem even when there is a big difference in the RI of the host versus the oil. The greatest impact will be found in stones like that above, where fissures lie perpendicular to the viewing angle.

Notes

Written in July 2020; published in two parts in Gems & Gemology (2020), Vol. 56, No. 3, Fall, pp. 443–444; No. 4, Winter, pp. 552–553.

References

- Hughes, R.W. (1998) Cloak and dagger: The politics of Opticon. GQ Eye, Vol. 1, No. 1, Fall, pp. 3, 6.

- Lotus Gemology (2015) Lotus Gemology lab alert for oiled gems. InColor. Spring, Issue 28, pp. 18–23.

About the author

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of several books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the Fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard and his wife and daughter's Ruby & Sapphire • A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of nearly four decades of work in gemology. In 2018, Richard was named Photographer of the Year by the Gem-A, recognizing his photo of a jade-trading market in China, while in 2020, he was elected to the board of directors of the Accredited Gemologists Association and was appointed to the editorial review board of Gems & Gemology and The Australian Gemmologist magazine. Richard's latest book, Jade • A Gemologist's Guide, was published in 2022.