An account of a 2013 visit to Mogok – Myanmar's fairy-tale wonderland.

Early each morning, Saw Sanda Soe, a young girl from a small village in Myanmar (formerly Burma), would begin the long walk to school. If it had rained the night before, others would join her. Not all were students, but each shared the same quest. Eyes were cast not towards heaven, but below, scanning the ground ahead. Occasionally one would stoop down for a closer look, before continuing. Rarely something would be slipped into a mouth or bag. As they made their way along the muddy road, each secretly hoped that the previous night’s rain had washed a bit of treasure across their path. For their village was special. It lay at the entrance Myanmar’s Mogok Stone Tract, home to the world’s finest rubies.

History

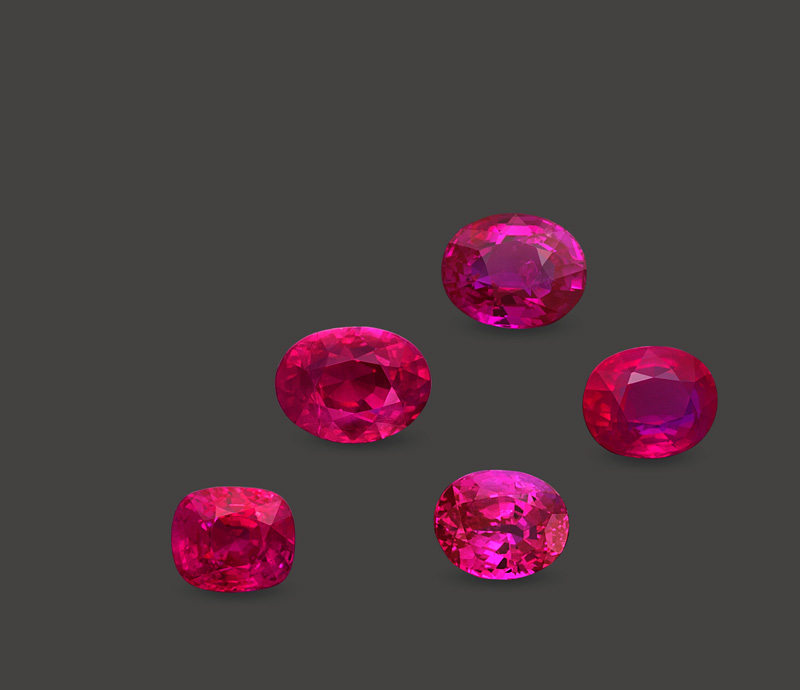

Rubies from the Mogok Stone Tract are the stuff of legend, and for good reason; more fine rubies have been clawed from the soil in this land than any other place on the planet.

The Shan originally settled the area in the 6th century AD. Their descendants still live there, now joined by a variety of other ethnic groups. In 1597 the King of Burma took over the mines from the Shan. He laid claim to all rubies above a certain size and/or value, which were to be turned over to him, on pain of death. When a “royal” ruby was found, a procession of soldiers and elephants would journey to Mogok to carry both the ruby and its finder to the capital, where the gem would be presented to the king.

Because of this, enterprising miners would break larger stones into smaller pieces that could be kept and sold. As in gem localities throughout the world, the most valuable stones were probably smuggled out (Thatcher, 1908).

By the late 19th century, European powers had entered Asia, including Burma. In 1886 the British took control of the area. London jeweler Edwin Streeter and N.M. Rothschild and the Exploration Co. won the tender and leased it to the Burma Ruby Mines Ltd., which took the lead in mining in the area.

The company brought in modern mining equipment, supplementing traditional methods (Hughes, 1997). They improved infrastructure, building roads, drainage tunnels and washing plants. In fact, the company discovered ruby not just in the mines, but also under the town of Mogok itself. So the British simply moved the town.

To facilitate this, the British company compensated those living on the land. But hoping to minimize costs, the British capped the price of compensation they would dole out, thus discouraging residents from building houses worth more than the cap. Therefore, if residents had to move, they would not have invested more in their property than they would be paid as compensation.

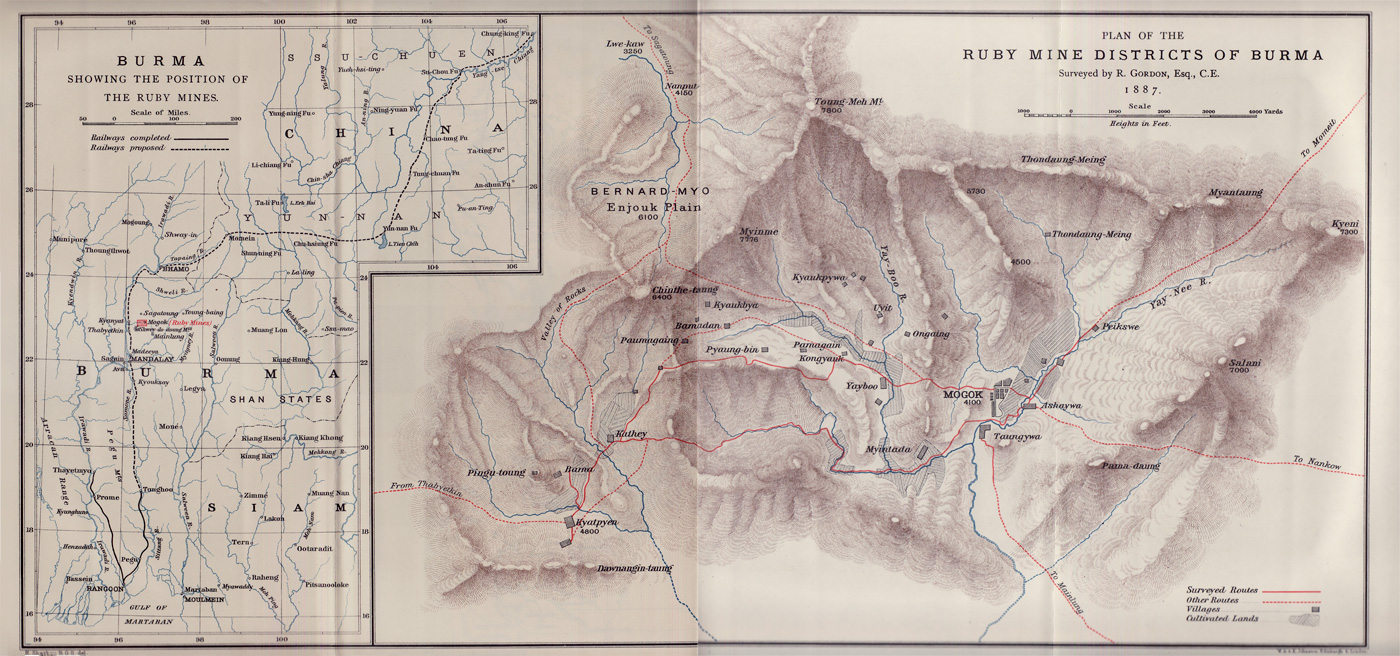

Figure 1. Map of Upper Burma and the Mogok Stone Tract. From Gordon (1888).

Figure 1. Map of Upper Burma and the Mogok Stone Tract. From Gordon (1888).

Even after moving the town and importing modern equipment, the company faced obstacles. As with the Burmese kings before them, the British suffered losses due to theft and were also hampered by flooding. Then the global marketplace was hurt by the introduction of synthetic ruby early in the 20th century. Burma Ruby Mines Ltd. surrendered their lease in 1931. After more than three decades, they had learned an important lesson: fine rubies are rare, indeed. At this point, mining reverted back to traditional methods (Kessel, 1960).

In 1962, political upheaval shook Mogok as the Burmese military took over the government. After this point, foreigners were banned from visiting the mines. By 1969 the junta nationalized the mining industry.

Figure 2. A “royal flush.” Five natural, unheated Mogok rubies from 3.02-4.02 ct. Specimens courtesy of Veerasak Gems. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Figure 2. A “royal flush.” Five natural, unheated Mogok rubies from 3.02-4.02 ct. Specimens courtesy of Veerasak Gems. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Off the Beaten Track

The Mogok Stone Tract is located in Kathe District of Upper Burma, 200 km northeast of Mandalay (Kyaw Thu, 2007). The Stone Tract area spans two valleys, the Kyatpyin Valley and, further east, the Mogok Valley, at about 1200 meters elevation (Keller, 1983).

Setting out to this remote area has never been easy. In the 19th century it was considered “almost inaccessible” and one had to journey by steamer and pony to enter the valley (Stewart, 1972). Later, after roads were built, four-wheel drive was a necessity due to poor conditions. There were also other dangers present. Early accounts from British travelers describe gangs of dacoits (bandits) that would intercept steamers on the river. The thick jungle surrounding the area was also a hindrance, containing disease-carrying insects, blood sucking leeches, and poisonous plants. If that was not enough of a deterrent, early visitors were told that the trees themselves were guarded by “malevolent spirits” (Gordon, 1888).

These may not have been the only spirits guarding Mogok’s rubies. The Burmese believe that after death some people become ote sa saunt, or guardians of the treasures. These supernatural beings often take the form of a beautiful woman.

An ote sa saunt is believed to come from someone who hides his or her treasures, including gold and gems, rather than leaving them for others. After passing away they become the guardians of the treasure.

Luckily, our group did not encounter problems. Access has improved considerably. In the early 1990s a paved road was constructed from Mandalay, and we reached the Mogok Valley within a day’s drive.

Recently a new road was finished via Pwin Oo Lwin (Maymyo), which cuts driving time down to approximately four hours.

Although the road conditions have improved, those at Mogok Stone Tract can prove challenging. On a few occasions we had to brave torrential rains, as our visit coincided with the monsoon. Some remote mines can still only be reached by four-wheel drive. At one location, even this was insufficient. After one of our trucks slid backwards down a slick dirt road, our team had to continue on foot.

|

Mogok “Lean-tos” Life in Mogok is certainly different than other places, as witnessed by the following story: A man began renovating his house. Over time, his neighbors began to notice changes – not to his house – but to their own. Gradually all the houses on his block began to tilt towards one side. The cause? While overhauling his own place, he discovered gem gravel (byon) directly beneath it, so dug up the foundation. But byon layers extend horizontally, as they represent ancient riverbeds. Thus in mining this vein, the effects of his “remodeling” project soon rippled down the street. Neighbors soon guessed what had happened, as it was not their first time. Welcome to life in Mogok, the city truly built on rubies. |

Figure 3. Wilawan Atitchat on the Mogok–Momeik road. Photo: E. Billie Hughes

Figure 3. Wilawan Atitchat on the Mogok–Momeik road. Photo: E. Billie Hughes

From Mine…

In former times, most mines in Mogok consisted of round (twinlon) or square (lebin) pits sunk into the soil in search of gem-bearing gravel, known as byon. These simple pits are rarely seen today; most mining uses open cast and quarrying methods.

The hmyadwin is a type of open pit mine where water is brought via channels to wash gravel on the hillside. In contrast to the twinlon, the hmyadwin is usually used during the rainy season because it requires a greater amount of water. When water is aimed at the hill, the lighter materials will float and be carried away while the heavier minerals, including gems, will remain where they can then be washed. Hmyadwin today often employ water cannons and modern separation jigs.

Another mining method involves miners searching the underground limestone caverns known as lu-dwin. These can be small crevices or deep caves spanning hundreds of meters and contain some of the richest byon in the Stone Tract. However, it can be treacherous. Miners must crawl through cramped spaces and risk cave-ins to retrieve the byon. This is the most dangerous type of mining, as the rocks are extremely wet and slippery. But it is also the most rewarding, for when a pocket of byon is found, it can hold an extremely high concentration of gems.

Quarrying is common today and involves miners tunneling directly into the mother rock. Explosives are often employed, but the method is fraught with problems, as blasting can damage the gems. With alluvial deposits being exhausted, this method has become more and more prevalent.

Figure 4. Mechanized open cast mine at Chaung Gyi. Photo: E. Billie Hughes

Figure 4. Mechanized open cast mine at Chaung Gyi. Photo: E. Billie Hughes

…to Market

After gems are recovered, some are sold as rough, while others are cut and polished first. There are several markets at different times and locations, with vendors moving from market to market throughout the day. Many vendors are actually descendants of the Nepalese Gurkhas that the British brought in to guard the mines.

The volume of goods can become overwhelming as sellers jostle to show their wares; it can be better to sit in a teashop, or better yet, a dealer’s office, and allow dealers to show stones one by one. This way the buyer can concentrate on each stone or parcel.

Markets run rain or shine, and on a drizzly day a row of umbrellas will line the streets to cover displays. Often stones will be set out on brass trays. Originally this was done because the yellow background enhances the red tones in ruby and spinel, but over time the custom became so ingrained that now even buyers go to the market with brass tray in hand.

Mogok’s open markets feature a range of items, including corundum, spinel, quartz, garnet and myriad other stones, both rough and cut. As with most markets, the vast majority is not worth buying; finer goods are almost always sold behind closed doors. And yet Mogok’s outdoor gem markets are one of the Stone Tract’s most colorful and interesting aspects, something that any visitor should try to experience.

Figure 5. Wimon Manorotkul (left) joins dealers displaying rough gems in Mogok’s market. Over fifty different types of gems are found in the Stone Tract. Photo: E. Billie Hughes

Figure 5. Wimon Manorotkul (left) joins dealers displaying rough gems in Mogok’s market. Over fifty different types of gems are found in the Stone Tract. Photo: E. Billie Hughes

Figure 6. A woman sorts stones in Mogok’s market. Brass trays were originally used to enhance the color of red stones, but have become so ubiquitous that now buyers bring their own brass trays. Photo: E. Billie Hughes

Figure 6. A woman sorts stones in Mogok’s market. Brass trays were originally used to enhance the color of red stones, but have become so ubiquitous that now buyers bring their own brass trays. Photo: E. Billie Hughes

Figure 7. Quarrying in Bawpadan, in Myanmar’s Mogok Stone Tract. Photo: E. Billie Hughes

Figure 7. Quarrying in Bawpadan, in Myanmar’s Mogok Stone Tract. Photo: E. Billie Hughes

Pondering Tomorrow

In today’s Myanmar, to say there is a new wind blowing is a vast understatement. No one could have predicted what has occurred in the past two years. One such sign is the reopening of the Mogok area to foreigners. Closed for as many as 40 of the past 50 years, the door to this magical land has once again been unlocked.

What we found is that, as mining continues, fewer and fewer stones remain. We saw little truly fine material; while better pieces always go straight to Yangon or abroad, production was clearly down from a decade ago.

Depletion of gem resources has pushed mine owners to rely more and more on mechanization. In some mines, this is supported with the help of foreign investment. Such mining methods are controversial, however. We were told that, prior to our visit, local residents had protested at one site, voicing concerns that unregulated mechanized mining would endanger the area’s water supply and overall environment. This forced the government to temporarily halt mining at that deposit. Such protests would have been unheard of even two short years ago, but are a further sign of changing times in Myanmar.

Whether such bans can be sustained is hard to predict. Mine owners argue that without mechanization, mining will be uneconomical. At Myanmar’s jadeite mines and western China’s nephrite mines, uncontrolled mechanized mining over the past decade has decimated both the environment and what is obviously a non-renewable resource.

Clearly there must be a middle ground. Regulations are needed that can protect both the environment and traditional mining customs, while still allowing locals to make a living. This does not have to mean a halt to all mechanized mining, but could be a set of guidelines to ensure that stones will be found for decades and centuries to come. This would protect not only the Mogok area and its unique culture, but also the global market that relies on Burmese ruby. Mechanized mining has long been banned in Sri Lanka and yet their gem industry thrives. Would this not be a worthy model to consider?

Dreamtime

Although mining methods have become more technologically dependent, superstitions remain. Saw Sanda Soe, daughter of mine owner Dr. Saw Naung U, described to the author a miner who had visions about hunting for gems. “Each time he had one of these dreams, he would tell my father that the mine’s spirit guardians are asking for donations. And after every offering, we would find stones.”

Offerings are not limited to underground angels. Mogok’s temples are often filled with rubies, spinels, sapphires and pearls, all left as donations to the deities. Indeed, the pagodas that dot the landscape are also built from charity.

Benevolence also extends to the mortal world. An important Mogok custom is that of kanasé, a centuries-old tradition that allows anyone to search the tailings of a mine and keep what they find. Nowadays, it is mainly women and children who continue the practice. Few stones of great size or value are found; even less today as production declines. Yet this custom gives common people hope – the dream of striking it rich – common to miners around the world.

Figure 8. A kanasé miner at In Byae, Mogok. Photo: E. Billie Hughes

Figure 8. A kanasé miner at In Byae, Mogok. Photo: E. Billie Hughes

Heavenly

Our group’s ascent from Mandalay to Mogok mirrored some of the experiences of earlier travelers to the Stone Tract. No, we did not have to take a steamer up river or fend off leopards and dacoits. But winding our way up curving roads into the dense jungles-clad mountains, we, too, experienced the wonder of discovery.

As we neared our goal, my father told me to expect something “just like Disneyland.” Sure, I thought, until we passed under a red arch that proclaimed Welcome to Rubyland. Off in the distance, barely visible through the clouds stood a stupa on a marble hill, looking uncannily like Sleeping Beauty’s castle. At that moment, I started to believe I really was entering one of the world’s most magical places.

The next day we set off for the mines. It was raining lightly, as it would do every day we were there. Making our way down the muddy dirt trail was tedious. It was not so much the rain that deterred us, but other obstacles. Every few meters someone ahead would stop and then stoop for a closer look.

Soon I was doing the same. As I walked along the path, a flash of pink winked from the mud. Bending down, I was delighted to discover a small crystal. It was a nattwe, a spirit-polished piece of frozen light. By now, our progress along the jungled slope had slowed to a crawl, each of us scanning the ground ahead, bowing in the hopes that our humility might impress the gods – perhaps just enough to be rewarded with a few fragments of treasure washed across our path. No, we were not off to school, but entering Myanmar’s Mogok Stone Tract. And we were in heaven.

References

- Anonymous (2013) Myanmar’s once restricted sites attract foreign tourists. Elevenmyanmar.com. 22 August. Accessed 26 October 2013.

- Gordon, R. (1888) On the ruby mines near Mogok, Burma. Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society, New Series, Vol. 10, No. 5, May, pp. 261–275; map, p. 324.

- Hughes, R.W. (1996) Pigeon’s blood. Momentum, Vol. 4, No. 13, Dec. 1996-Feb. 1997, pp. 18–21.

- Hughes, R.W. (1997) Ruby & Sapphire. Boulder, CO, RWH Publishing, 512 pp.

- Keller, P.C. (1983) The rubies of Burma: A review of the Mogok Stone Tract. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 19, No. 4, Winter, pp. 209–219.

- Kessel, J. (1960) Mogok: The Valley of Rubies. Trans. by Rodway, S., London, Macgibbon & Kee, 198 pp.

- Kyaw Thu (2007) The igneous rocks of the Mogok Stone Tract. Palaminerals.com. Accessed 26 October 2013.

- Shwe War Lwin (2013) After 10 years, Mogok set to open up. Myanmar Times, 27 October 2013. Accessed 4 October 2013. <https://www.mmtimes.com/index.php/national-news/8115-after-10-years-mogok-set-to-open-up.html>

- Stewart, A.T.Q. (1972) The Pagoda War. The Ruby Mines. London, Faber & Faber, pp. 140-144.

- Thatcher, F. (1908) Where rubies are pebbles. The World To-Day, Vol. 15, No. 5, November, pp. 1142–1148, 5 photos.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the following individuals for their assistance: Hpone-Phyo Kan-Nyunt of Gübelin Gem Lab for helping to organize our latest visit to Mogok in July 2013; Dr. Ei Ei, who helped guide us in Mogok; Saw Sanda Soe, who shared her stories of growing up in Mogok; Ko Ye Aung Myo, Ko Than Htwe, U Thein Htay, U Win Maung, all of Mogok.

About the author

E. Billie Hughes visited her first gem mine (in Thailand) at age two and by age four had visited three major sapphire localities in Montana. A 2011 graduate of UCLA, she qualified as a Fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (FGA) in 2013. An award winning photographer and photomicrographer, she has won prizes in the Nikon Small World and Gem-A competitions, among others. Her writing and images have been featured in books, magazines, and online by Forbes, Vogue, National Geographic, and more. In 2019 the Accredited Gemologists Association awarded her their Gemological Research Grant. Billie is a sought-after lecturer and has spoken around the world to groups including Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels. In 2020 Van Cleef & Arpels’ L’École School of Jewellery Arts staged exhibitions of her photomicrographs in Paris and Hong Kong.

Notes

First published in InColor magazine, Fall/Winter 2013, pp. 40–45.